Every adult carries a quiet script that tells the brain whether the world is safe or threatening. That script was first drafted in the first few months of life, when a baby learns whether a caregiver will be reliably present or absent. When we speak about “attachment,” we are really talking about those early emotional blueprints and the way they echo through our friendships, romances, families, and workplaces.

If you’ve ever noticed that you repeat the same relational patterns, that certain conflicts feel disproportionately intense, or that you sometimes feel “stuck” in a particular role, attachment theory gives you a language for those experiences. More importantly, attachment‑based therapy offers a concrete, compassionate pathway to rewrite those scripts, giving you the freedom to relate to yourself and others in healthier, more satisfying ways.

John Bowlby argued that humans are biologically programmed to seek close emotional bonds. For an infant, a responsive caregiver functions as a “secure base” from which the child can explore the world and to which they can return for comfort. When that base is consistently available, the child learns that they are worthy of love and that others can be trusted.

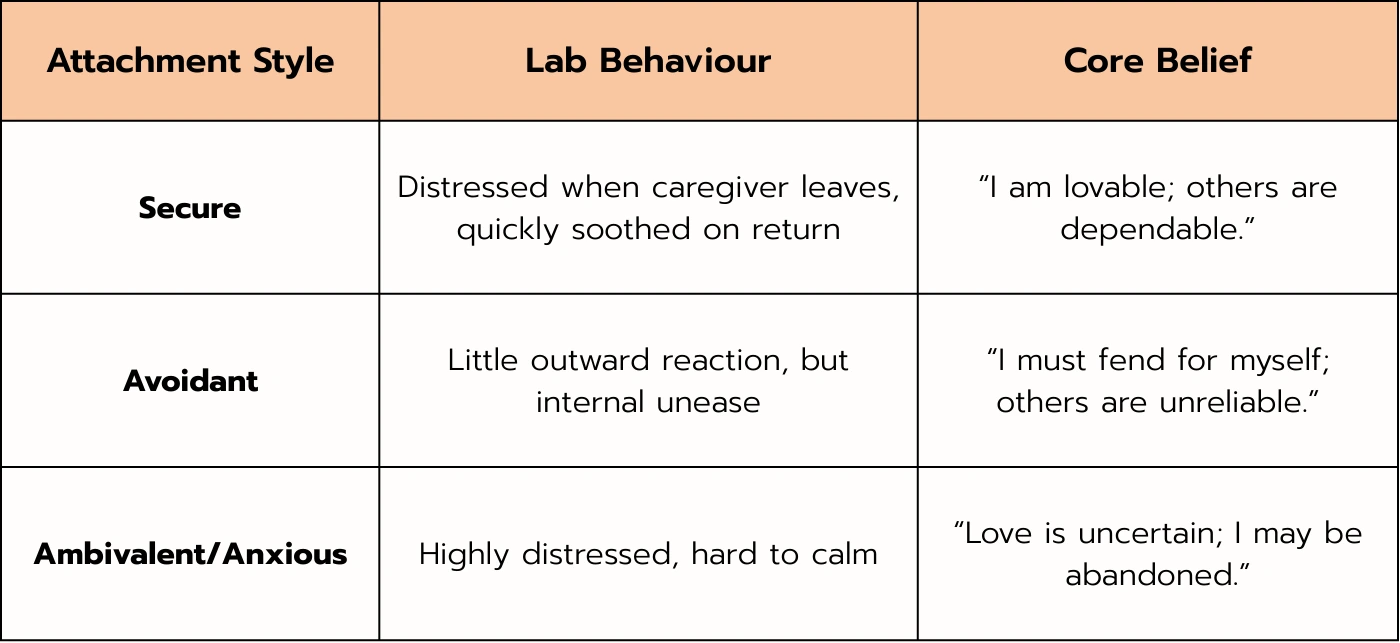

Mary Ainsworth observed toddlers in a brief separation‑reunion experiment and identified three primary attachment styles:

Later research added a fourth style disorganised attachment often seen in children who have endured trauma, neglect, or chaotic caregiving.

Bowlby called the mental representations formed from these early interactions internal working models. They are subconscious maps that tell us whether we can trust ourselves and others. Although they develop early, they are not immutable; new relational experiences can update them.

Attachment‑based therapy is a form of psychotherapy that focuses specifically on how early relational experiences influence present‑day thoughts, emotions, and behaviours.

It is not the same as “attachment therapy” used with children in some residential settings; rather, it is a collaborative, adult‑oriented approach that respects the client’s autonomy and aims to create a new secure relational experience within the therapeutic relationship.

Core premise: Therapy becomes a temporary or ongoing secure base, a safe, attuned space where the client can explore painful memories, test new ways of relating and receive corrective emotional experiences. Over time these experiences help remodel the internal working models that once dictated fear, avoidance, or hyper‑dependence.

Although the process is fluid and tailored to each client’s readiness, most clinicians move through three overlapping phases that together foster insight, re‑parenting, and relational integration.

Purpose: Bring hidden scripts into conscious view.

Methods:

Outcome: Increased awareness of how early experiences still colour present perceptions, and a sense of empowerment that comes from naming the past.

Purpose: Provide the nurturing that was missing or inconsistent in childhood, thereby weakening the grip of maladaptive internal models.

Methods:

Outcome: The client learns to meet their own emotional needs, reducing reliance on others for validation and soothing.

Purpose: Apply newly acquired self‑knowledge to real‑world connections.

Methods:

Outcome: More authentic, reciprocal relationships; the client can recognise when old scripts arise and consciously choose a healthier response.

Trauma is an overwhelming experience – real or perceived – that exceeds a person’s capacity to cope, leaving the nervous system stuck in a state of hyper‑arousal or shutdown.

It is not limited to war, violence, or natural disasters; everyday events such as chronic neglect, emotional invalidation, or repeated micro‑aggressions can also be traumatic when they persist over time.

The classic survival responses that become automatic patterns in adulthood.

Chronic tension, headaches, digestive issues, or unexplained pain.

Sudden anger, numbness, or pervasive anxiety.

Intrusive memories, flashbacks, or difficulty concentrating.

Hyper‑vigilance, avoidance, or “trauma bonding” (clingy, dependent ties to an abusive or unreliable person).

These reactions are the nervous system’s attempt to protect the self, but when they remain unchecked they sabotage healthy attachment.

When a person repeatedly experiences intermittent reward (affection, attention) mixed with fear or neglect, the brain can form a trauma bond – a paradoxical attachment that feels both comforting and harmful.

Grounding, breath work, and establishing a predictable routine.

Revisiting the traumatic memory in a controlled way, often using Free processing, imagery re-scripting or EMDR‑style techniques.

Re‑building secure relationships, developing new coping skills, and envisioning a future beyond the trauma.

Healing is rarely linear; setbacks are normal and can be reframed as opportunities to practice new skills.

The therapist’s consistent, attuned presence offers a corrective relational experience that the client may have missed in childhood.

Helping the client label what they felt (fear, shame, helplessness) restores a sense of agency.

By revisiting the traumatic event and inserting a compassionate adult figure, the client can rewrite the internal story from “I was powerless” to “I survived and am now learning to be safe.”

Providing the validation, protection, and love that were absent, which directly counteracts the disorganised attachment often produced by trauma.

Somatic techniques (grounding, progressive muscle relaxation) help regulate the nervous system, reducing freeze or fawn responses.

In the third phase, the client practices healthier ways of relating—assertive communication, boundary setting, and mutual attunement—thereby dismantling trauma bonds and rebuilding secure connections.

Healing does not stop when the session ends. Clients are encouraged to nurture the new neural pathways they have begun to forge:

These habits act like maintenance for the secure base you have cultivated in therapy.

Many of us inherit relational habits without even realising it. A parent who grew up feeling unseen may unintentionally overlook their child’s emotional cues, perpetuating insecurity across generations. Recognising this intergenerational transmission is the first step toward breaking it.

Spotting the pattern (“When my partner gets angry, I shut down, just like my father did”).

Consciously offering warmth, consistency, and validation to those we care about.

Engaging in therapy, support groups, or parenting workshops to learn new relational skills.

When we rewrite our own attachment story, we become the secure base our children or anyone we love need.

If any part of this article resonated with you, whether you recognised a familiar relational pattern, felt curiosity about your childhood influences, or simply want to deepen your connection with yourself and others, I would be honoured to walk alongside you.

You can explore more about my approach and book a free 30‑minute introductory session.

Together we can:

Remember, the past does not have to dictate your future. With curiosity, compassion, and the right support, you can create a new relational blueprint that honours your worth and nurtures genuine connection.

Take a moment now: What relational script feels most familiar to you? Is it the tendency to withdraw, to cling, or perhaps to oscillate between the two? Recognising the script is the first line of the story you can rewrite.

If you’d like to explore this further, feel free to reach out. I look forward to the possibility of supporting your journey toward greater security, intimacy, and peace.